|

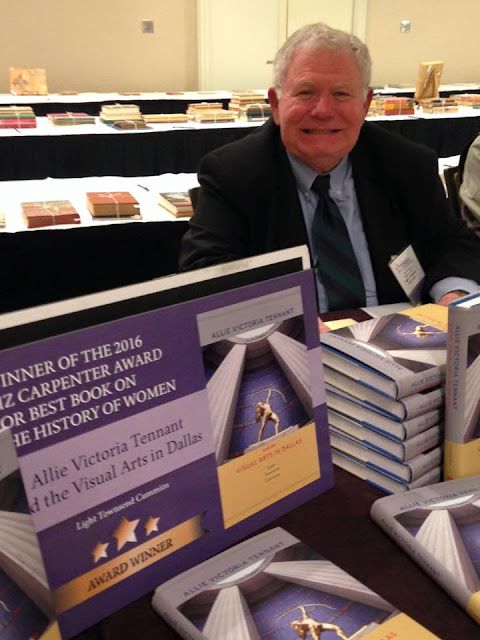

| Allie Tennant, 1942 |

The answer is simple: the research.

It was fun to accomplish the research for this book because I

was “the historian as detective,” as the late Robin Winks once entitled a classic

book he wrote on the subject of historians and their research.

Allie Tennant left no personal papers or writings. As well,

during her own lifetime she was a private person who consistently avoided being

the center of attention. Having never married, she lived her entire adult life in

the company of several bachelor brothers and had few close friends, although

she led an active life in Dallas society and had many acquaintances.

Tennant was a tireless worker in many civic causes that

promoted the visual arts while she also had a long career as a sculptor. She established

a well-known public presence in Dallas during her lifetime because of these

activities, but seldom talked about herself to others and left no written

records explaining herself.

The lack archival materials on her part means she today is a

person without a historical voice. She does not speak through any documentary

sources to historians who want to write about her.

It is therefore flatly impossible to document her thoughts,

opinions, or any of the personal reasons why Tennant did the things she

accomplished in her career. Given this, no historian can pull back the curtain and

look inside at her persona to determine what was in her mind as the motivations

for her work or how she conceptualized the life she lived. Such things are absolutely

beyond the pale for any academic history of her life.

Does this mean that Allie Tennant is not a proper candidate

for a biography? And, if one is written about her, would such a biography be a priori deficient because it could

never elucidate the human personage who engaged in her career, explain her personality

for the reader in a meaningful way, or offer windows into the workings of her

mind?

In my opinion, these are absolutely not impediments –

especially for a biography written in the genre of academic history.

Academic historians are concerned with finding and

explaining historical significance. Their central concern is: Why is the present

the way it is today because of what happened in the past?

My research about Allie Tennant asks only that question, and

nothing else. Such an orientation is the case for many, if not most, other academic biographies written about people important to Texas history, male and female.

Because almost nothing has been written about Tennant since

her passing in 1971, I found doing the research for this book -- in my effort to

answer the question of significance – to have been an operation of historical

recovery almost archeological in nature. I currycombed public records, read

hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles about her, ferreted out much information

about her from the files and historical collections of the organizations to

which she belonged, and spent much time going through the archival collections

of people with whom she corresponded.

I also conducted considerable research about the visual arts community in Dallas during her lifetime, especially the artists with whom she associated, the women's clubs in which she was active, and the organizations such as the Museum of Fine Arts which she supported. As noted in the preface and in the title of the book, I purposely devoted much space in the volume to discussing the evolution of that artistic community in order to provide a full context for Tennant's career and public life. This book is therefore as much about the growth of the visuals arts community during Tennant's career as it is about her because one cannot be isolated from the other.

I also conducted considerable research about the visual arts community in Dallas during her lifetime, especially the artists with whom she associated, the women's clubs in which she was active, and the organizations such as the Museum of Fine Arts which she supported. As noted in the preface and in the title of the book, I purposely devoted much space in the volume to discussing the evolution of that artistic community in order to provide a full context for Tennant's career and public life. This book is therefore as much about the growth of the visuals arts community during Tennant's career as it is about her because one cannot be isolated from the other.

All of this research permitted me to present for the first

time anywhere the complete story of her public career while it afforded me the

opportunity to explain her historical significance. She was historically

important as an artist, an arts educator, a thirty-year trustee of the Dallas

Museum of Fine Arts, an active promoter of the visual arts in Dallas women’s

clubs, and as a long-time supporter of the State Fair of Texas in addition to a

variety of related civic causes. Most of this constitutes information new to the historical literature on the arts and culture in Texas.

In short, Allie Tennant played a significant role in shaping

the visual arts community in Dallas and in helping to make the city a cultural

center. These proved to be important historical contributions on her part.

Granted, because of my research, I did better come to understand

the person who was Allie Tennant in a human sense, but such realizations constitute

unsubstantiated opinions on my part which go beyond the impersonal documents I consulted.

They are opinions rooted in conjecture only, not the “stock-in-trade” in which

academic historians willingly deal. The assigning of historical significance

and the presentation of conjecture are most certainly not hand-maidens in dual

support of the historian’s work. The former is important for historians while

the latter is consistently rejected by them.

These are ultimately distinctions of no matter to me because

I found the detective work in reconstructing Allie Tennant’s public career alone

to have been delight enough during this project. That research is what I most

enjoyed about doing this book.